Course: Genocide and Group Hostility

Module 4: Group Hostility

What is group hostility and its relevance to genocide? How does it manifest through hate speech?

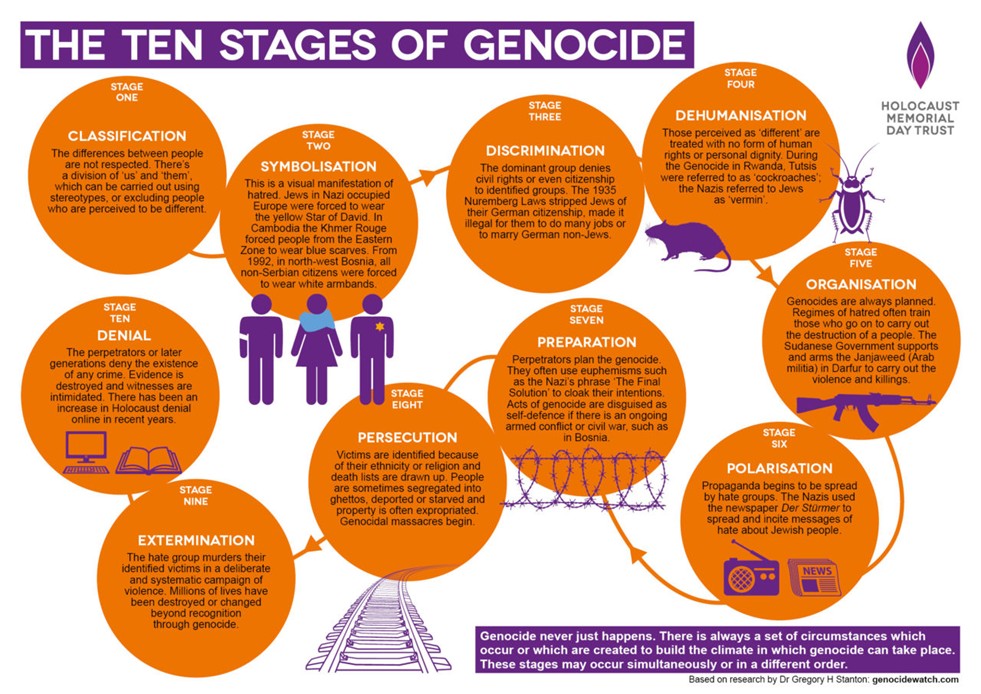

This module examines how group hostility develops and the role of narratives in perpetuating prejudice. By looking at historical and more recent cases of genocide, we will explore how group hostility could ultimately lead to dehumanization and eventually trigger and legitimize genocide. Dehumanization could be seen as a necessary, though not sufficient, precondition for genocide. We will first explore some of the leading causes of genocide.

Causes of genocide

Genocide is not an isolated event. It stems from a combination of political, social, and economic factors. These often include a history of discrimination, dehumanizing ideologies, unequal power relations, and the deliberate use of fear to divide and control ethnic communities. Understanding these multiple causes helps reveal how such tensions can escalate to mass violence.

Research on why genocides happen is abundant in the field of comparative genocide studies, with numerous studies addressing causes, risk factors, and motivations at both the macro and micro levels. Research at the macro level typically focuses on political leadership and societal risk factors (autocracy, nationalist ideology, war) (read more). At the micro level, the focus is on perpetrators, their motivations, and psychological explanations (read more).

To know more about the various stages of genocides, visit this page from the Holocaust Memorial Day trust.

Read more here for a useful collection of publications on the multiple causes of genocides.

Dehumanization

The intent to destroy a specific population typically emerges from a military conflict and/or violent ideology.

Portraying a specific group in a way that denies their humanity due to their religious, ethnic or national identity serves to legitimize exclusion, hate crimes, persecution, and in the worst case, genocide.

Genocide is prefigured by the definition of a certain group as alien or dangerous. “They” are portrayed as beasts, scum, infidels who threaten “our” existence: It is either “us” or “them”. Dehumanization of “the other” can be seen as a necessary, though not the only, precondition for inciting in-group members to destroy fellow human beings simply because of their identity.

The horrors of the Holocaust laid the foundation for the perception of genocide as a distinct and particularly reprehensible crime that the international community should “prevent and punish” (UN Genocide Convention of 1948). There are significant differences in the political context, specific characteristics, and scope of mass murder identified as genocide. Nevertheless, there are some common features. Genocide is defined as the attempt to destroy a group because of their religious, national or ethnic identity. Revealing such intent distinguishes genocide from other mass atrocities such as crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing.

Historical and more recent cases of genocide provide examples of how perpetrators attempt to dehumanize the targeted victim group to legitimize mass atrocities. The Nazi attack on Jews and Roma is but one such example. ISIS labelled the Yazidis “devil worshippers” as they attempted to destroy this religious minority group in 2014.

Past genocides have often been fuelled by specific rhetoric used against a target group:

- Yazidi (ISIS): Devil worshippers, heretics

- Tutsi (Hutu): animal references (snakes, cockroaches)

- Roma/Jews (Nazi): racially inferior, inherently criminal

Narrative approach

The narratives that distinguish between “us” and “them” are often based on religious, ethnic, social, national, or other divides. They may be inclusive or exclusive.

For instance, minority groups encounter a range of online hate narratives that target them based on their religion, nationality, or gender. These discourses frequently employ metaphors, unsavoury comparisons, and symbols designed to dehumanize or stigmatize members of the groups.

One strategy to counter such rhetoric is to use positive counter-narratives. This approach involves presenting stories and messages that directly challenge stereotypes by offering alternative perspectives and fostering inclusion. Hate narratives could be a key driver of group hostility, shaping perceptions and fueling exclusionary attitudes. Understanding these narratives provides insight into how prejudice affects different groups, from racial to religious communities.

(To read more: browse the topic Hate speech and media literacy)

Group Hostility and Stereotypes

As part of identity development, we inadvertently advance an “us” versus “them” discourse. Such narratives are often based on religious, ethnic, social, national, or other divides. For example, before and during the Srebrenica genocide, expressions of hatred and group hostility flourished in public discourse in the region. The Yugoslav Wars of Succession were fought along ethnic and religious lines.

Group hostility refers to the systemic incitement against specific minority populations, promoting their discrimination and exclusion. Racism, antisemitism, homophobia, and ableism (prejudice against individuals with disabilities) are all forms of group hostility that began as dehumanizing narratives and stereotypes.

Group hostility perpetuates prejudice and discrimination, targeting entire communities based on perceptions of shared characteristics. Differentiating between types of hostility allows for more targeted approaches to understanding and addressing the challenges faced by minority communities and their members.

A Gender Perspective on Group Hostility

Group hostility can be caused by multiple factors, with gender affecting its probability, severity, and extent.

Genocidal attacks on women and girls display the misogyny of the perpetrators. In the ICTR case against Nahimana, Barayagwiza and Ngezi –usually referred to as “the media trial”–the Chamber reviewed the publications containing anti-Tutsi propaganda, and in convicting the accused, determined that “the presentation of Tutsi women as femmes fatales focused particular attention on Tutsi women and the danger that they represented to the Hutu. This danger was explicitly associated with sexuality. By defining the Tutsi women as an enemy in this way, Kangura articulated a framework that made the sexual attack of Tutsi women as foreseeable.”

In this film, the Yazidi woman Ashwaq talks about her experience during the Yazidi genocide, where she was enslaved by ISIS, and how she confronted her perpetrator in an Iraqi court.

Hate Speech

Hate speech may be sanctioned or used by state representatives and other political actors, intentionally or unintentionally legitimizing discrimination against vulnerable groups. Hate speech may fuel tensions and even lead to perpetrating mass atrocities.

The United Nations defines “hate speech” in its 2019 Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech as follows:

“Any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor.”

This definition highlights the diverse forms hate speech can take and underscores the importance of addressing it within specific cultural and contextual frameworks.

Hatred against Religious Groups

Hate speech does not necessarily amount to the dehumanization associated with genocide and other mass atrocities. However, hate speech and other manifestations of group hostility based on religious and/or ethnic identity can be warning signals towards a potential escalation into atrocity crimes.

- Antisemitism refers to negative attitudes and actions directed against Jewish people, both as a collective and as individuals. It has deep historical roots and manifests in various forms, including conspiracy theories, stereotypes, and narratives that portray Jewish people as a societal, economic, and political threat to society.

- Anti-Muslim racism denotes prejudice and discrimination targeting individuals or communities perceived to be Muslim. It often relies on narratives that associate Islam with violence or extremism, which can contribute to fear and exclusion of Muslim members of the community.

(To read more: browse the topic Hate speech and media literacy)

Role of Social Media in Hate Speech

Online hate speech is a growing challenge. Opinions on what constitutes online hate speech vary across specific cultural and legal contexts.

Hate speech on digital platforms often spreads rapidly due to the anonymity and speed of online communication. It can perpetuate hostility towards minority groups by using harmful narratives, symbols, and memes to sow divisions and incite violence.

Combating hate speech and group hostility with media literacy

Understanding how media is produced and processed can help with combating online hate speech and group hostility.

Hate speech and education

Hate speech is a phenomenon that individuals can encounter early in life, often in social settings such as schools. Therefore, teachers and educators can intervene early to help reduce potential harm. One way to do this is to challenge and avoid stereotypes.

Questions for reflection and discussion

- What warning signs associated with hate speech targeting specific religious or ethnic groups could indicate a risk of escalation into more severe atrocity crimes?

- Reflect on dehumanization as a precondition for genocide using specific examples.

- Case study discussion: Identify statements made by state leaders or politicians that could be classified as hate speech or even an attempt at dehumanization before and during genocides. You may refer to the material included in this course (see Modules 1, 2, and 3) or to public discourse related to these cases.

For Educators

- When teaching about group hostility, make sure that no group under discussion is unwittingly presented through common stereotypes.

- Be careful about presenting individual students in class as representatives of an entire group.

- Perpetrators are still human despite their actions, so avoid teaching that demonizes them, also to avoid reducing genocide to individual traits.

- For more resources, consult our For Educators page.

Additional Resources

Group hostility and dehumanization

- ICHR topic page: Group Hostility

- Bradshaw, Samantha. 2024. “Disinformation and Identity-Based Violence”. Stanley Center for Peace and Security. (link)

- Hoffmann, Christhard, and Vibeke Moe. 2020. The Shifting Boundaries of Prejudice. Scandinavian University Press. (link)

- Døving, Cora Alexa. 2020. “‘Love Your Folk’: The Role of ‘Conspiracy Talk’ in Communicating Nationalism.” Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft MbH & Co. KG EBooks 7 (January): 189–202. (link)

Hate speech and social media

- ICHR topic page: Hate Speech and Media Literacy

- Bilewicz, Michał, and Wiktor Soral. 2020. “Hate Speech Epidemic. The Dynamic Effects of Derogatory Language on Intergroup Relations and Political Radicalization.” Political Psychology 41 (1). (link)

- Lenz, Claudia, Sanna Brattland, and Lise Kvande, eds. 2016. Crossing Borders: Combining Human Rights Education and History Education. LIT Verlag. (link)

- United Nations. 2019. A/74/486: Report on online hate speech. (link)

- United Nations. 2021. Hate speech ‘dehumanizes individuals and communities’: Guterres. (link)

- Vasist, Pramukh Nanjundaswamy, Debashis Chatterjee, and Satish Krishnan. 2023. “The Polarizing Impact of Political Disinformation and Hate Speech: A Cross-Country Configural Narrative.” Information Systems Frontiers 26 (April): 1–26. (link)

Tools for educators

You have reached the end of the course Genocide & Group Hostility.

Congratulations on completing this online course!

We appreciate your time, effort, and dedication throughout the course. We hope the knowledge and insights you have gained will continue to inspire and guide you in both your work and personal growth. Thank you for being part of this journey, and we look forward to your future endeavours in promoting inclusive citizenship and upholding human rights.

We also extend our gratitude to our regional partners and all other contributors for their invaluable support in developing this course. This course was developed in collaboration with various experts. We also thank the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) for their financial support.

The editorial team –

Ingvill T. Plesner (main editor), Neha Philip, Andrea Cocciarelli, Sidsel Wiborg